Technical Desktops

| 500 Series Selection: |

| Name: 9000/520 | |

| Product Number: 9020 | |

| Introduced: 1982 | |

| Division: Engineering Systems | |

| Ad: Click to see, Click to see, Click to see | |

| Original Price: $28250 | |

| Catalog Reference: 1984, page 603 | |

| Donated by: Stan Kurzet, Newport Beach. Bob Niland, Enterprise Kansas (BASIC manuals). |

Description:

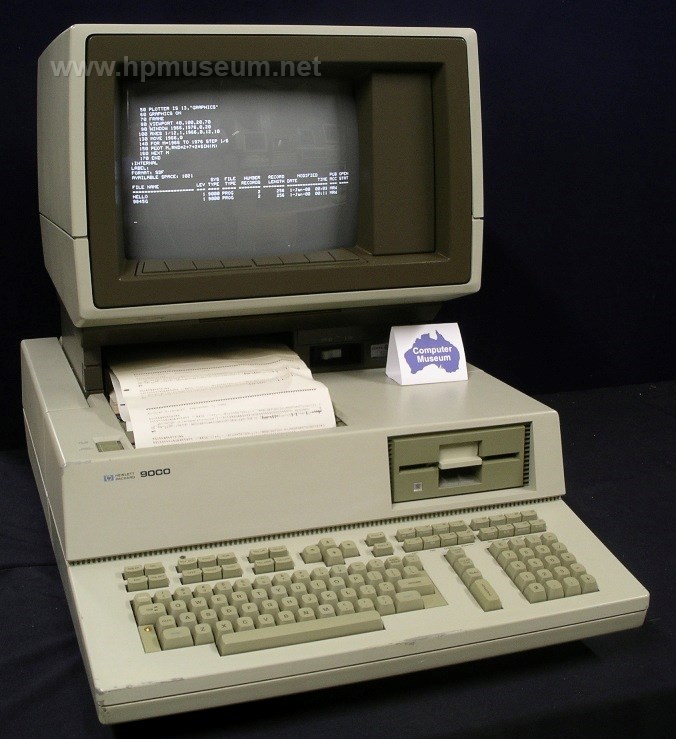

The 9020A was the first of the 500 Series computers. When compared to its contemporaries of the time, the 9020 was probably the most advanced workstation ever introduced by HP.

The 9020 came in three models. The 9020A had a 12-inch color monitor with 512 x 390 resolution. The 9020B had a 12-inch monochrome monitor with 560 x 455 resolution. The 9020C ($39,885) had a 13-inch color monitor with 560 x 455 resolution.

All models came standard with a 5.25-inch floppy disc drive, at least 512K RAM and a 4-slot backplane. Most units shipped with the built in optional 10 MB hard disc and internal thermal printer. These machines could be expanded with additional memory and additional CPUs. The top-of-the range 9020T included the color monitor, hard disc, 1 MB RAM, printer, BASIC, HP-UX, Fortran and Pascal for only $65,585.

In July of 1983, HP's Boeblingen Computer Products Division introduced a detachable keyboard option (G02, $600) for the 9020.

The 1000/A900 and 9000/500 Series computers were so fast, they were bound by special US government export restrictions. Automatic export approval was given for only 16 countries. Export to any other country required an individual license.

The 9020 workstation was also the heaviest ever made by HP. These computers weighed between 55 and 74 Kg depending on configuration.

Collector's Notes:

The museum's 9020 has been an interesting challenge. Our unit has the built-in hard disc with BASIC installed. We copied the contents to an external drive (7958) in SDF format. Most other HP computers will not perform file functions (eg CAT or COPY) on SDF discs. So, we also copied the contents of the internal drive in LIF format. LIF does not accept files with names longer than 10 characters. So, a number of files from our 9020 did not copy over. We manually copied some of the files over one at a time by reducing the length of the file names. But, we didn't get them all. Unfortunately, the system files for the 9020 do not appear when a CAT command is sued. These files are hidden. We were unable to boot our 9020 from the external hard disc onto which the files had been copied.

In the meantime, we ran a utility on the 9020 named BOOT_TO_FILE. We have no documentation on the utility, but the screen says that it will write the operating system from your hard disc to a file that you name. We succeeded in writing our 9020's system to an external file (SDF format. It won't write to a LIF disc). The file that was created is a DATA file. We moved the file to an external hard disc and tried to boot from it but without success. Another step must be required to make a bootable system from the DATA file. During this process, we learned that the 9020 will work with a 9122C and write to HD floppy discs (the hardware support matrix we have notes the 9122C as untested). We have successfully archived the DATA file that we created when we ran the BOOT_TO_FILE utility.

In our continuing effort to archive workable system software, we ran another utility that we found on our 9020 named MARK_BOOT (also with no documentation). The screen for this utility says that it will look at connected discs for installed operating systems and allow the user to mark those operating systems as "loadable" or "unloadable". When we ran this utility, it automatically marked the operating system on our 9020's internal disc as "unloadable". Between projects, we powered our 9020 down before running the utility again to mark our internal disc O/S as "loadable". Unfortunately, our 9020 would not boot from its internal disc when we powered it back up.

This problem was fixed in November of 2010 thanks to Charlie Brett of Fort Collins, Colorado. Charlie donated his collection of 500 Series software, which enabled us to boot our 9020 from its floppy drive.

The 520, 530 and 540 all use the same power supply module. As of 2015, two of the three power supplies at the museum are fully functional. We do not have a schematic for the power supply and are keen to acquire one.

A problem that afflicts all 9020 computers is battery corrosion under the keyboard. The four rechargeable AA batteries that maintain non-volatile memory are soldered directly to the keyboard PCB. These batteries should be removed/replaced right away. It is common for keyboards to not function because of the corrosion over so long a period.

As of 2015, we had two 9020 computers at the museum. Both have the 98770 high-resolution color monitor. Only one of the monitors works. The other monitor never worked and shows many signs of excessive heat. However, we successfully swapped the high-voltage board from the dead monitor into the good monitor to resurrect it when it failed.

9000/520 Story From Bill Reed:

In early 1982, I was assigned to the staff of Commander, Carrier Group Eight in Norfolk, Virginia. The commander, at that time, was Rear Admiral Jerry O. Tuttle who was into all things communications, command, and control. Some found him a hard man to work for but he was a bonafide visionary bordering on genius. I admired him.

As a staff, we had been using two HP 9845Bs to run a few classified decision aids, that is, programs that helped examine aspects of a tactical situation and helped to devise a tactical decision of use in that scenario. The 9845s helped but were limited and terminally flawed by their tape storage systems.

It wasn’t long after that the staff went to a war game in Newport RI, an annual east coast event. HP was demonstrating a new, prototype computer, the 9000/520 series. When the staff returned to Norfolk, we immediately contacted the local HP rep. Through a number of contacts and, probably, high pressure salesmanship, CCG8 was given access to five, fresh-off-the-assembly-line HP 9000s/520s. They were awesome by comparison to everything else on the market. The admiral loved the light pen option.

I was brought into the process as the fourth member of the staff action team that consisted of the Chief of Staff, the Ops and Plans Officer, and a contract PhD assigned to help with analyses of a variety of tactical and developmental situations and, then, the development of an integration of all the other things the 9845s were doing into the 520. I was invited to join the team as I had criticized the order that was being placed. Expensive as they were, our 9000s were ordered with minimal memory, single CPU, single 10mb hard drives, and Rocky Mountain BASIC. I made the case to modify and add to what was there. The BASIC was added as the operating system was the only thing offered as part of the package in those early days of the 9000 series. In fact, I do not believe HP had even begun to market the 9000s at that time.

As a staff, our mission was to train carrier groups for deployment. These typically included one aircraft carrier, on which we would embark, and a variety of cruisers, destroyers, and, occasionally, submarines. We would “work” the battle group up with various tactical scenarios and end their training sessions with a multi-week fleet exercise. We would then disembark allowing a tactical carrier or cruiser commander, also an admiral with staff, to deploy with the group. As a staff, we typically trained two or more exercises and battle groups a year. In my first year, we spent 330 days at sea. It was an optimal environment for development, experimentation, and analysis. It was a perfect environment for our tactical computer system’s growth.

We set about accumulating every tactical computer software program available in the U. S. Navy, typically products developed by contractors or naval laboratories. We had in excess of 70 programs. The integration of those aids with previously never seen tactical displays and extensions went way beyond radar, Naval Tactical Data System (NTDS), or anything else that anyone had ever seen. We brought entire families of informational message traffic into the systems’ databases, automatically. Using the HP interfaces, we networked multiple computers together. As our admiral had somewhat of a reputation for the visionary and a modicum of unconcerned bravado. People in the Atlantic fleet began calling the system JOTS for Jerry O. Tuttle’s System.

Almost every tactical commander who saw the JOTS system wanted one. The 9000s were pricey but the software that we developed used the early multitasking abilities of its operating system to run displays and up to six or seven decision aides that had been rewritten to use common and appropriate data bases, running simultaneously. The contributions by the brain trust of about 12 tactical and fleet staff members worked at improving JOTS. This body of “experts” was critical. By the time JOTS was noticed by the Pentagon, Rear Admiral Tuttle had moved on to a new assignment. But, the Pentagon wanted a demo. What did you “officially” call it? "Tuttle's system" wouldn't fly. My suggestion was to give the fledgling system a “joint” title as the joint services’ philosophies had just begun and had great traction. Since JOTS had nothing to do with Army, Air Force or Marine Corps functions, this idea was probably a stretch. My suggestion was the "Joint Operational Tactical System", or JOTS by another definition. It stuck.

It might seem odd but the Rocky Mountain BASIC remained the language of choice. It was easier for non-programmer contributors to work with. At one point, JOTS had nearly two dozen “partitions” and well in excess of a million or more lines of compiled code. JOTS was also noticed by Great Britain’s Royal Navy as something they were interested in. They had designs on the software but wanted to run it on more sophisticated computers. They had a preference for a more powerful, mini-mainframe computer made popular by the now defunct Ferranti Ltd.

Despite the fact that some naval leaders didn't see the point of JOTS, at one time, almost every tactical or fleet staff in the United States Navy had five or more HP 9000s, often networked together. Some had the early projection systems for common displays. There was a sharing of the load, so to speak. The computers gave those that processed anti-submarine warfare what they wanted on one terminal while those involved with anti-air warfare processed on another computer. The technology that ensued included special interface boards capturing radar systems, communications systems and aircraft systems, many connected with fiber optics.

Eventually, HP 9000s were available in sufficient numbers to be used for other things of tactical need. In 1985, one of my projects used a 9000 to analyze fleet broadcast communications. The system incorporated an interface card which was built by a Navy Laboratory and was capable of reading 16 channels of any fleet’s broadcasts into the computer for parsing and measurement using BASIC software that I wrote. The computers were also used for intelligence work, early terrain mapping, and the like.

Although I was reassigned to another staff in mid 1984, I remained in the loop with JOTS for nearly three years. The Navy Department, after getting over the fact that an upstart fleet initiative using HP desktops was actually as good as or better than the those designed by contractors for the next generation of command and control, decided to convert JOTS to a more efficient language. This effort was referred to as ITDA, or Integrated Tactical Decision Aid. The conversion would be undertaken by professional navy lab personnel and programmers. ITDA became an interest of ARPA and a number of other agencies. It was dubbed as a form of “expert system” artificial intelligence in 1986. It was shortly after this heightened interest that my association with the system ceased. I was assigned to a new job as executive officer of a ship. When I departed, JOTS was still running on HP 9000/520s everywhere.

Epilogue: Rear Admiral Tuttle, JOTS's creative force, retired as a vice admiral and Deputy Chief of Naval Operation for Command, Control, Communications, and Electronic Warfare. Rear Admiral James H. Flatley, III, Admiral Tuttle’s relief on CCG8, pushed the system to the Navy Department level and retired a number of years later. Vice Admiral Joe Metcalf, then Commander, Second Fleet, was a big proponent of the system as were a majority of senior officers. But, there were some who remained less interested. Without the help of the Navy Lab system and innumerable officers and staffs, such an effort would not have been possible. But it was the power and versatility of the 9000/520 systems that allowed us to prosper.

| Back | More Images | Product Documentation | Category Accessories |

^ TOP©2004 - 2025 BGImages Australia - All Rights Reserved.

The HP Computer Museum and BGImages Australia are not affiliated with HP Inc. or with Hewlett Packard Enterprise. Hewlett Packard and the HP logo are trademarks of HP Inc and Hewlett Packard Enterprise. This website is intended solely for research and education purposes.